- Home

- Gill, Anton

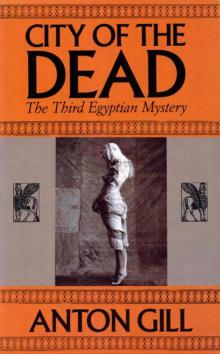

City of the Dead

City of the Dead Read online

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

MARTIN ALLEN IS MISSING

HOW TO BE OXBRIDGE

THE JOURNEY BACK FROM HELL

BERLIN TO BUCHAREST

CITY OF THE DEAD

The Third Egyptian Mystery

ANTON GILL

BLOOMSBURY

First published in Great Britain 1993

This edition published 1994

Copyright © 1993 by Anton Gill

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd, 2 Soho Square, London W1V 5DE

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 7475 1757 6

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21

All rights reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Typeset by Hewer Text Composition Services, Edinburgh

Printed in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading

for Joe Steeples

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The historical background to the story which follows is broadly correct, but the majority of the characters are fictional. We know a good deal about ancient Egypt because its inhabitants were highly developed, literate, and had a sense of history; even so, experts estimate that in the 200 years since the science of Egyptology began, only twenty-five per cent of what could be known has been revealed, and there is still much disagreement about certain dates and events amongst scholars. However, I do apologise to Egyptologists and purists, who may read this and take exception to such unscholarly conduct, for the occasional freedoms I have allowed myself.

THE BACKGROUND TO HUY’S EGYPT

The nine years of the reign of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun, 1361-1352 BC, were troubled ones for Egypt. They came at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the most glorious of all the thirty dynasties of the empire. Tutankhamun’s predecessors had been mainly illustrious warrior kings, who created a new empire and consolidated the old; but just before him a strange, visionary pharaoh had occupied the throne: Akhenaten. He had thrown out all the old gods and replaced them with one, the Aten, who had his being in the life-giving sunlight. Akhenaten was the world’s first recorded philosopher and the inventor of monotheism. In the seventeen years of his reign he made enormous changes in the way his country thought and was run; but in the process he lost the whole of the northern empire (modern Palestine and Syria), and brought the country to the brink of ruin. Now, powerful enemies were thronging on the northern and eastern frontiers.

Akhenaten’s religious reforms had driven doubt into the minds of his people after generations of unchanged certainty which went back to before the building of the pyramids one thousand years earlier, and although the empire itself, already over 1,500 years old at the time of these stories, had been through bad times before, Egypt now entered a short dark age. Akhenaten had not been popular with the priest-administrators of the old religion, whose power he took away, or with ordinary people, who saw him as a defiler of their long-held beliefs, especially in the afterlife and the dead. Since his death in 1362 BC, the new capital city he had built for himself (Akhetaten - the City of the Horizon), quickly fell into ruin as power reverted to Thebes (the Southern Capital; the northern seat of government was at Memphis). Akhenaten’s name was cut from every monument, and people were not even allowed to speak it.

Akhenaten died without a direct heir, and the short reigns of the three kings who succeeded him, of which Tutankhamun’s was the second and by far the longest, were fraught with uncertainty. During this time the pharaohs themselves had their power curbed and controlled by Horemheb, formerly Commander-in-Chief of Akhenaten’s army, but now bent on fulfilling his own ambition to restore the empire and the old religion, and to become pharaoh himself — he did so finally in 1348 BC and reigned for twenty-eight years, the last king of the Eighteenth Dynasty, marrying Akhenaten’s sister-in-law to reinforce his claim to the throne.

Egypt was to rally under Horemheb and early in the Nineteenth Dynasty it achieved one last glorious peak under Rameses II. It was by far the most powerful and the wealthiest country in the known world, rich in gold, copper and precious stones. Trade was carried out the length of the Nile from the coast to Nubia, and on the Mediterranean (the Great Green), and the Red Sea as far as Punt (Somaliland). But it was a narrow strip of a country, clinging to the banks of the Nile and hemmed in to the east and west by deserts, and governed by three seasons: spring, shemu, was the time of drought, from February to May; summer, akhet, was the time of the Nile flood, from June to October; and autumn, peret, was the time of coming forth, when the crops grew. The ancient Egyptians lived closer to the seasons than we do. They also believed that the heart was the centre of thought.

The decade in which the stories take place — a minute period of ancient Egypt’s 3,000-year history - was nevertheless a crucial one for the country. It was becoming aware of the world beyond its frontiers, and of the possibility that it, too, might one day be conquered and come to an end. It was a time of uncertainty, questioning, intrigue and violence. A distant mirror in which we can see something of ourselves.

The ancient Egyptians worshipped a great number of gods. Some of them were restricted to cities or localities, while others waxed and waned in importance with time. Certain gods were duplications of the same ‘idea’. Here are some of the most important, as they appear in the stories:

AMUN

The chief god of the Southern Capital, Thebes. Represented as a man, and associated with the supreme sun god, Ra. Animals dedicated to him were the ram and the goose.

ANUBIS

The jackal god of embalming.

ATEN

The god of the sun’s energy, represented as the sun’s disc whose rays end in protecting hands.

BES

A dwarf god, part lion. Protector of the hearth.

GEB

The earth god, represented as a man.

HAPY

The god of the Nile.

HATHOR

The cow goddess; the suckler of the king.

HORUS

The hawk god, son of Osiris and Isis, and therefore a member of the most important trinity in ancient Egyptian theology.

ISIS

The divine mother.

KHONS

The god of the moon; son of Amun.

MAAT

The goddess of truth.

MIN

The god of human fertility.

MUT

Wife of Amun, originally a vulture goddess. The vulture was the animal of Upper (southern) Egypt. Lower (northern) Egypt was represented by the cobra.

OSIRIS

The god of the underworld. The afterlife was of central importance to the thinking of the Ancient Egyptians.

RA

The great god of the sun.

SET

The god of storms and violence; brother and murderer of Osiris. Very roughly equivalent to Satan

SOBER

The crocodile god.

THOTH

The ibis-headed god of writing. His associated animal was the baboon.

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS OF CITY OF THE DEAD

(in order of appearance)

Fictional characters are in capitals, historical characters in lower case.

Tutankhamun: Pharaoh, 1361—1352 BC

Ay: His wife’s grandfather. Co-regent

Akhenaten: The disgraced recent predecessor of Tutankhamun, now known as the Great Criminal

Horemheb: Co-regent with Ay and rival to the succession Ankhsenpaamun (Ankhsi): Tutankhamun’s Great Wife

Tey: Ay’s C

hief Wife

Nezemmut: Horemheb’s wife

HUY: Former scribe

TAHEB: Shipowner. Widow and heiress of Huy’s friend Amotju

KENAMUN: Police chief. Former priest-administrator in the Southern Capital

AHMOSE: Courtier

NEHESY: Chief huntsman

SHERYBIN: Charioteer

INENY: Ay’s secretary

Zannanzash: Hittite prince

MERINAKHTE: Doctor

HORAHA: Chief doctor

SENSENEB: His daughter

HAPU: His steward

AAHETEP: Nehesy’s wife

NUBENEHEM: Brothel keeper

ONE

The king bit his lip. The interview had gone badly. He watched the general’s retreating back with murder in his heart. How much longer would he have to put up with the curbs of this ambitious old man?

To begin with, he had been grateful for Horemheb’s experience, and he had leant on him. But it was four floods since his coronation, and at seventeen years old, he was still pharaoh in name only. The army, his spies told him, remained loyal to Horemheb, its commander since the days of his predecessor, the disgraced pharaoh Akhenaten. He would have to work on getting them to transfer their loyalty to him. Then he would see about sending Horemheb off on a diplomatic mission to some remote province. He toyed with the idea of assassination, but knew that the day when he felt secure enough to have that done was still far off.

Then there was Ay, even older, but just as ambitious, and as much of a thorn in his side. The king was well aware that both these men — joint regents in doubtful alliance during his minority — wanted only one thing — to wear the pschent themselves. He made a point of having the red-and-white double crown of the Black Land placed on his head at every meeting with his two advisers, as they now liked to be called, though down the years General Horemheb, the stronger of the two, had got the young king to confer a greater string of titles on him than any commoner had ever carried in the entire history of the country, and that stretched back through one and a half recorded millennia, and eighteen dynasties.

Ay had been Akhenaten’s father-in-law. Another commoner. The son of a Mitannite whose sister had the good fortune to become Great Wife of Menkheprure Tuthmosis, grandfather of Akhenaten, he had put it about — and the pharaoh could not disprove it — that he was also the brother of Tiy, Akhenaten’s; mother. Ay had further consolidated his position in the royal household by marrying off his daughter Nefertiti to Akhenaten. The girl, the most beautiful ever seen in the Black Land, became the king’s Great Wife, by whom he produced seven daughters. The present king was married to the third daughter, who had much of her mother’s beauty. But the family net Ay had woven around the young pharaoh had not endeared him.

‘I am king. Nebkheprure Tutankhamun.’ He said his name to himself as the high steward removed the heavy crown and replaced it with a blue-and-gold headdress — lapis and gold leaf over a light leather frame. The king sniffed the leather, enjoying the smell. His name gave him confidence. He wanted it on the people’s lips, on columns, pylons, temples and city gates. He would be the redeemer of the country, the man who would bring the Black Land back its glory after the sombre years of failure and doubt which had preceded his reign. But, he thought angrily, returning to his original theme, to be entered as such a king in the papyri of the scribes of history, he would first have to emerge from the shadows of his ‘advisers’. And, if he was to found a dynasty that would sweep aside all remaining doubts about his own remote legitimacy of descent, and therefore his own claim to the throne, he must have a son. So far, in the five years of marriage that had passed since Ankhsenpaamun grew capable of motherhood and they had started to share a bed, they had not even been able to produce a girl. He had no doubt of his own powers — he had two sons and three daughters by concubines already — but their claim to lineage was not strong enough, and he had no illusions about their chance of survival if he were not there to protect them against the cunning Ay and the predatory Horemheb.

How could two old men thwart him like this? Horemheb was all of fifty-five, and Ay ten years more than that. Yet they were as thirsty for power as men half their age. The king supposed that the lust stemmed from years of frustration, but their ability to survive was borne out by the fact that after the fall of Akhenaten they had emerged not only with their careers intact but in key positions of power which they had immediately and ruthlessly consolidated. Tutankhamun himself was in no doubt at all that they had brought about the fall and the death of the old king, though even to consider killing the pharaoh was on a level of blasphemy to start the demons of Set howling.

He made himself calm down. What was needed above all to combat these two was a clear head. He had few friends and they were all his age or younger. Inspecting the stables a few days earlier, where he was showing off his new Assyrian hunting horses to a group of young barons, he had been surprised by a visit from Horemheb, who, with his usual mock servility, had requested a meeting. Horemheb had not come alone into the presence of his king, but had the arrogance, then as always, to arrive flanked by half a dozen of his special Medjays. Tutankhamun had felt like the leader of a schoolboy gang surprised raiding date palms by the farmer. The memory irritated him to such an extent that even now he clenched his teeth and balled his fists, as he wished the general a violent death. Tear out his eyes! But as soon as the image was past, Tutankhamun cursed himself for not being able to maintain his decision for even a moment to keep cool blood.

Snapping his fingers for wine, he told the major domo that he wished to be washed and made-up afresh. The interview with Horemheb had unsettled him, and it had come hard on the heels of new information from his spies which had been even more perturbing. They had revealed a plan of Ay’s — though nothing could be substantiated — to marry Ankhsenpaamun, if anything should happen to him.

He knew that this was merely a political contingency plan: marrying the dead king’s wife would strengthen his successor’s claim. Ay already had a Chief Wife, Tey, Nefertiti’s stepmother, to whom he had been married for as long as anyone could remember, and to whom he appeared to be devoted. But the thought that Ay could contemplate outliving him disturbed Tutankhamun; and as for the idea of Ankhsi having to go to bed with a man fifty years her senior, it was too disgusting to contemplate. The king wished that he were ten years older himself. Then he would be able to outmanoeuvre these two crocodiles who had been experienced sons of guile before the Eight Elements which formed him had joined in his mother’s birth-cave.

He told himself that Ay’s plan would come to nothing. He had even half begun to devise a plan to neutralise Ay by spreading a rumour in Horemheb’s camp that the old Master of Horse was plotting against him. He was doubtful of its success. Horemheb appeared to need Ay to balance his own power game; just as the little crabs that scuttled in and out of their holes along the bank of the river held up an enormous claw and a minute one.

It was not outside the bounds of possibility that Horemheb would use Ay to catch him in a pincer movement, thought the king, as the little crabs scuttled out of his heart to give way to consideration of the meeting he had just had with the general. Anger bubbled up again as he remembered that Horemheb had turned his back before leaving the audience chamber; but Tutankhamun managed to control it this time.

Horemheb had come alone, for once. His proposal had been outrageous. The king had requested — requested of a subject! — time to consider, but in reality he knew that there was little he could do to prevent it. The general wanted to marry Nezemmut.

The pincer movement again. For a moment of panic, the king saw himself outmanoeuvred on the senet board, saw himself dispensed with before he had begun to reign. Nezemmut was now twenty-four. She had never had quite the beauty of her older sister Nefertiti, but she had a far more durable character, and she had ridden out the storm following the fall of Akhenaten without recourse to her father’s protection. She had a dark, strong face, her eyes full of sexual cha

llenge and threat. If Nefertiti’s looks reminded you of the sky, Nezemmut’s made you think of the earth.

She had been married to a son of the Hittite king Selpel, but the marriage was annulled after the Hittites withdrew their friendship from the Black Land. Since then, she had lived in the palace at the City of the Horizon, and her affair with the sensitive picture painter, Auta, was an open secret mildly disapproved of by the king. With the collapse of the city, Tutankhamun had brought her back with him to the Southern Capital as part of his retinue - and, as he now remembered with another little stab of irritation, at Horemheb’s suggestion.

How deeply laid were the general’s plans? And how patient was he? The king could see immediately that a marriage to Nezemmut would strengthen a future claim to the throne by Horemheb. The girl would be preferable to any of Akhenaten’s surviving daughters - the younger ones were now at marrying age - because the stigma of being related by blood to the Great Criminal did not attach to her. As body servants brought water in a golden bowl and washed his face and arms, the king’s thoughts turned uneasily to his own connivance at the blacking of Akhenaten’s name. It had been necessary to underpin his own legitimacy as pharaoh; and of course the campaign had been planned, engineered and executed by Horemheb, riding roughshod over Ay’s weak objections at the vilification of his former son-in-law. At the time, Tutankhamun had believed that Horemheb was simply helping him; giving the line of succession the sort of boost it needed after so much chaos and uncertainty. Now, looking back, it seemed to the king that Horemheb had been helping himself. He appeared to be nothing but another one of the general’s tools. As long as he accepted that role he would be safe for as long as the general chose; but if he resisted...

City of the Dead

City of the Dead